This is a review of the made-for-television film A Man for All Seasons (1988)

directed by and starring Charlton Heston as St. Thomas More. It is based on Robert Bolt's play of the

same name and is not to be confused with the 1966 version starring Paul

Scofield. The 1988 version is available on DVD and is available from the usual outlets.

I have read several reviews of the 1988 version. They invariably compare it with the 1966 film, some

preferring one and some the other. One or the other critic fails to realize that Heston was

no stranger to the play -- he was More in several off-Broadway and U.K.

performances just as Scofield was More on the West End and Broadway.

Personally, I much prefer the 1988 Heston version which,

among other things, is more faithful to the script of the play (including the "common man" and the Spanish ambassador characters ).

Some reviewers complain that Heston did not resemble More

physically while they imagine that Scofield did. I am not so sure that is true but even if it were, the inner man

is more important than the externals.

In my view, Heston conveyed the persona of More more accurately than Scofield, whose More was aloof and rather condescending. The real More was humble in the truest sense of the word and thoroughly engaged in everything in his

environs -- from the pets he kept (including a monkey) to his natural and acquired children and their spouses, to his own feisty mate Lady Alice, to his father and brother-in-law and

many friends, to the citizenry of London whom he served in various legal

capacities, to the Church and to the England that cost him his life.

Of central importance is that the Heston

version, being more faithful to the play, provides thought-provoking dialogue

about More's views of law and conscience upon which one can reflect.

"Again [in Bolt's play, More]

says: 'God made the angels to show Him splendor—as He made animals for

innocence and plants for their simplicity. But man He made to serve Him

wittily, in the tangle of his mind.' Not in the pride and certainty of the

individual conscience, but in the tangle of his mind."

A

viewer of the film should remember this or he may become confused by the film's

several references to More's "private conscience". In fact, More's

conscience was not "private" -- it was Catholic.

As

Peter Ackroyd suggests in his profoundly moving biography of More, the very word

"conscience" implies thinking or knowing "with" (con). Thinking with the Church is the essence of More's conscience.

In

the First Things article, Judge Bork points out that the idea of a individual, private conscience is a Protestant

view, not a Catholic one: In fact, to

Judge Bork, "More’s behavior may be seen as submission to external

authority, a conscious and difficult denial of self."

While in a sense one's conscience is "private" in that each individual bears responsibility for his moral actions, we have a duty to form our conscience in accordance with the teachings of the Church.

Here

it is illuminating to quote from the saint himself -- from his response when he was being coerced to agree with Henry VIII's repugnant policies.

More

referred to the church militant elsewhere in Christendom and to the church

triumphant in heaven. Then he asked whether he was bound to conform his

conscience "to the Council of one Realm against the general Council of

Christendom". Thus we see that in More's own view his conscience

was anything but private; it was formed by and answered to the teachings of the

universal Church. Its locus was eternity.

See

the movie and think on these things; they are as relevant now as they were

nearly 500 years ago.

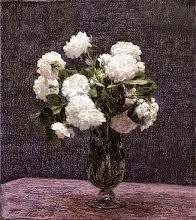

Image: Thomas More and his daughter Meg in his cell in the Tower of London by John Rogers Herbert, 1844. From Wikimedia Commons. In the public domain.

No comments:

Post a Comment