Babettes Gæstebud (1987), better known by its English title, Babette's Feast, is a color film set in the late 1800s in village on the coast of Jutland in Denmark. The motion picture is based on a short story of the same name by Danish author Karen Blixen (also known as Isak Dinesen). Gabriel Axel, another Dane, directed the movie, which stars Stéphane Audran as Babette.

Martine (Birgitte Federspiel) and Philippa (Bodil Kier) are the only children of a widowed Danish minister who is the founder of an austere pietistic Lutheran sect. The daughters are named after Martin Luther and Luther's friend, Philipp Melanchthon.

A Swedish military officer, Lorens Löwenhielm (Jarl Kulle), and a French opera star, Achille Papin (Jean Philippe La Font), briefly court the sisters in their youth. Löwenhielm withdraws because he believes himself unworthy of Martine, and Philippa rejects Papin after he makes a pass while giving her voice lessons in the parlor of her father's home.

The father dies, and the sisters -- who never marry -- spend their adult lives doing good works and holding together the sect founded by their father. One stormy night, when the sisters are no longer young, a French widow, Babette, comes to their home with a letter of introduction from Papin, explaining that she had to flee France for political reasons.

After some initial hesitancy, the sisters take Babette into their home as their cook and housekeeper. Babette enlivens the home and the community, adding herbs and special dishes to their bland diet and a French playfulness to transactions with the grocer and fishermen.

After more than a decade, Babette's quiet life with the sisters changes when the French lottery ticket bought for her yearly wins 10,000 francs. The sisters assume Babette will return to France, and she considers it but decides to remain with them and spend her money providing a feast for the 100th anniversary of the birth of the women's deceased father.

Frightened by the arrival of the quail and a huge sea turtle that are to be made a part of this feast, the sisters and members of the sect are reticent about the meal. At the request of his aunt, who is a respected member of the sect, Löwenhielm joins the party. Married to a noblewoman and having won favor in the Swedish court by dropping pious sayings learned while courting Martine, Löwenhielm is now a General. His praise of the food and wine overcomes the timidity of the others, who partake of the glorious repast Babette provides.

Löwenhielm remembers the haute cuisine at the Cafe Anglais in Paris prepared by a woman chef. He makes a speech incorporating the Psalm he once heard in Babette's home when her father was alive. "Mercy and truth have met each other: justice and peace have kissed." (Ps. 84:11 in the Douay-Rheims Bible.) The Church understands this to be a reference to Christ's unity of person but it is not presented that way by Löwenhielm.

The strange and wonderful food and drink weakens the psychological boundaries of the sect members. Old grudges seem to resolve and longstanding worries seem to dissolve. The sect members conclude the evening by dancing around a well the way Danes dance around the tree at Christmas.

Afterward, Babette admits she was the chef at the Cafe Anglais to whom Löwenhielm referred. She tells the sisters that she has spent all she had on the feast and will remain to work for them. No one in France who meant anything to her is still alive anyway, so there is no point in going back.

In reflecting on the film, one wonders how long in real life the bliss would have lasted for the sect members since it was produced by the rich meal and wine to which they were unaccustomed. It seems likely that the next morning they would have been more than a little embarrassed by their behavior and felt as if they had not quite been themselves.

As Christians, we know that good food and good wine do not have the power in themselves to bring lasting change in the human soul, which is comprised of the intellect and the will. Thus, either the supposed transformation of the sect members was only transitory, or something supernatural occurred.

Many Catholics and other Christians think the film has a profoundly Christian message. Catholics see it as affirming the goodness of creation against a heretical Manicheanism. Many see the meal as Eucharistic and Babette as a Christ-figure, sacrificing herself for the good of others. One author sees the film as portraying Luther's theology of grace. Another sees it as epitomizing the theology of Kierkegaard.

Even granting a measure of latitude for "artistic license", however, the film is a poor metaphor for Holy Thursday. The essence of Holy Thursday was Christ's institution of the priesthood and Holy Communion, empowering the priest -- through an act of consecration -- to transform bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ for consumption by the faithful. In Babette, there is no priesthood, no words of consecration, and hence no transubstantiation; there is only a meal. A Last Supper that is only a meal might be considered sacred by some Protestants but surely not by orthodox Catholics.

While the well-intentioned but floundering sect members needed the sacramental graces of the Church, one wonders if the Babette enthusiasts are not projecting their own views onto a film where the director, and the author of the short story on which the film was based, might have intended something entirely different than a Eucharistic metaphor.

Those who see the feast as Eucharistic make much of Babette's supposed sacrifice, but there was no sacrifice. Babette's art was cooking, and spending her money to create a memorable meal was an indulgence, not a sacrifice. Near the end of the film, Babette admits that the meal was done at least in part for her own gratification, saying, "It was not just for you", meaning it was for herself as well, and that an "artist is never poor". In the short story, this is even clearer: Babette says, "For your sake? . . . No, for my own."

Much is also made of the fact that there were twelve at the dinner table. Interestingly, there were only 11 until Löwenhielm was invited. Thus, the number symbolism -- if any was intended -- is a reversal of the Last Supper, where there were 12 until Judas's betrayal, then only 11. But, perhaps there is no symbolism at all. Many believe twelve is the perfect number for an elegant dinner party.

In the film, Papin talks about how some day Philippa will sing in heaven, and Philippa tells Babette that in heaven she will delight the angels with her cuisine. Aside from the fact that angels do not have bodies to delight with food, one might consider that if singers and chefs focus on their art in heaven, then heaven is merely a continuance of life on earth and might as well be achieved by science.

Remember that a metaphor is first and foremost a figure of speech, which implies that there is a speaker who is using the figure. The "speakers" in the film were Karen Blixen, the author of the short story, and Gabriel Axel, the director of the film.

According to a website devoted to Karen Blixen, she came from a Unitarian family and her religious views were consonant with those of the Danish existentialist Søren Kierkegaard, who did not believe in an ecclesial relationship to God. Also, ironically given the food theme, Blixen had stomach problems, was perhaps anorexic, and died of malnutrition or starvation.

The Blixen site says the Babette story is about "pietism and the sensuality of food". (Pietism is a religious current that emphasizes personal piety rather than church membership and participation in the sacraments.)

Here are two quotes from Blixen's short story on which the film was based:

"Of what happened later in the evening nothing definite can here be stated. None of the guests later on had any clear remembrance of it. They only knew that the rooms had been filled with a heavenly light, as if a number of small halos had blended into one glorious radiance. Taciturn old people received the gift of tongues; ears that for years had been almost deaf were opened to it. Time itself had merged into eternity. Long after midnight the windows of the house shone like gold, and golden song flowed out into the winter air."Based on the above quotes from the short story, it seems that Blixen did see her characters as having received some kind of grace that night, although it is difficult to distinguish what she describes from the predictable effects of a good meal and an abundance of wine. Perhaps Blixen meant to describe the natural grace of which good food is a part, or perhaps she meant the diners received a transitory supernatural grace. There is nothing, however, to suggest that Blixen intended the dinner to be a metaphor for the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, as the Catholic Babette enthusiasts maintain.

"When later in life they thought of this evening it never occurred to any of them that they might have been exalted by their own merit. They realized that the infinite grace of which General Löwenhielm had spoken had been allotted to them, and they did not even wonder at the fact, for it had been but the fulfillment of an ever-present hope. The vain illusions of this earth had dissolved before their eyes like smoke, and they had seen the universe as it really is. They had been given one hour of the millennium."

As for Gabriel Axel, he is a gourmand married to a French woman. Axel once told an interviewer that his wife could prepare all the dishes from Babette's Feast. In 1968, Axel made a feature length motion picture called Danish Blue. The title does not refer to blue cheese but to blue movies. It is a propaganda film advocating the legalization of pornography. According to the Wikipedia entry:

"The film mixes interviews, reconstructions and fiction in playful fashion, seeking to ridicule and undermine Denmark's censorship laws at the time. The film may be said to have been successful in its mission, since a year after its release Denmark completely legalized pornography.I am neither a theologian nor an expert in film or literature, but I believe that insofar as the story and film might be about more than art and food, Blixen and Axel's intended message was one of naturalism -- the idea that beatitude can be attained by natural means. That, of course, is a beatitude without the beatific vision. Such an interpretation fits with Blixen's statement that the sect members that night had "been given one hour of the millennium" (during which Christ rules on earth -- something that Catholics do not take literally), and with Axel's promotion of pornography, which I suppose he mistakenly believes makes for a psychologically healthier society.

"The film was banned in France but released in both England and the USA. It started a whole wave of documentary films about pornography in Denmark."

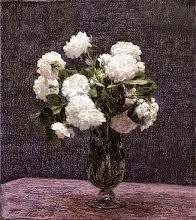

In short, I do not believe that Babette's Feast has a Catholic or even a generic Christian message. It does, however, have lovely cinematography and an enjoyable glimpse of 19th century Swedish style in the interior of Löwenhielm 's father's home. For these, I give the film three roses.

No comments:

Post a Comment