Sunday, September 26, 2010

St. Vincent and the Ravens

Those interested in St. Casilda might wonder about the identity of the "San Vicente" after whom the waters where Casilda obtained her miraculous healing were named.

"San Vicente" refers to St. Vincent, the 4th century martyr whose feast day is January 22. Near where St. Casilda was healed, there was once a monastery dedicated to St. Vincent. That is how the waters there came to be named after him.

St. Vincent was born at Huesca in Aragon in northeastern Spain. He served as a deacon in Zaragosa, which is also in northeastern Spain on the Ebro River. And, he was martyred under the Roman Emperor Diocletian in the eastern coastal city of Valencia in 304.

In the proceedings that resulted in his martyrdom, Vincent was brought to trial along with his bishop, Valerius. It is said that because Valerius had a speech impediment, Vincent spoke for both himself and the bishop. The Roman governor became so angry because Vincent was very outspoken and fearless that he had Vincent tortured and killed, whereas he only exiled the bishop.

There is a tradition that after Vincent's martyrdom, ravens protected the saint's body from being devoured by wild animals until his followers could recover it. St. Vincent's remains were then taken to what is now known as Cape St. Vincent. A shrine was erected over his grave and flocks of ravens continued to guard it.

In 313, less than 10 years after Vincent's martyrdom, the Emperor Constantine legalized Christianity throughout the Roman Empire. But, by the 5th century the Roman Empire had disintegrated.

Next, the Visigoths ruled Spain. Partly through the efforts of Isidore of Seville (560-636) and his brother Leander, around 589, the Visigoth King Reccared and his nobles converted from Arianism to Catholicism. Around 600, the Visigoths began building the Cathedral of Córdoba dedicated to St. Vincent. The people of Visigothic Spain were very devoted to St. Vincent.

The Moors conquered Spain in 711. The Arab geographer Al-Idrisi called St. Vincent's shrine "Kanīsah al-Ghurāb" (Church of the Raven) because of the ravens that guarded it.

Later during the 700s, the Moors took the Cathedral of Córdoba dedicated to St. Vincent through a forced acquisition and used parts of it to build the Great Mosque of Córdoba, constructed between 784 and 987.

During the 1100s, King Alfonso I of Portugal had St. Vincent's remains exhumed and transferred by ship to a monastery in Lisbon named after the saint. Both the flag and the coat of arms of the city of Lisbon show the boat that carried St. Vincent's remains there and the ravens that guarded them

The Córdoba mosque was re-taken by the Christians in 1236 and once again became a Cathedral. The re-conquest of Spain was largely completed by 1238 and entirely accomplished in 1492 by the Catholic Kings, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile.

Source:

Adapted from the Wikipedia article, "Vincent of Saragossa", supplemented by additional sources.

Image:

Stained glass window depicting St. Vincent Martyr (left, holding the palm of martyrdom) and St. Casilda. From the shrine of St. Casilda near Briviesca. Both saints have always been venerated at the shrine.

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Casilda of the Rising Moon (Borton, 1967)

Casilda of the Rising Moon is an historical novel about the life of Casilda, an 11th century saint. The book is authored by California-born Elizabeth Borton de Trevino, a convert to Catholicism. The dust jacket says the book is intended for ages 12 and up.

The book was published first in hard cover in 1967 and a paperback followed. Both are out of print but can be purchased second-hand through the usual outlets.

Borton's tale begins with teenage Casilda, a Moorish princess, living in the palace of her father, the Muslim king of Toledo, whom Borton calls "King Alamun". Borton gives Casilda a half-sister, Princess Zoraida, and a half-brother, Prince Ahmed. Borton makes Casilda's father an Arab while describing her mother as a Berber who died giving birth to Casilda. Other principal characters include Sulema, the nurse to both girls, and Ismael Ben Haddaj, a Muslim prince of Jewish ancestry who falls in love with Casilda while Casilda's sister, Zoraida, falls in love with him.

Borton takes the reader through the familiar incidents of Casilda's life -- her concern for her father's Christian prisoners, her secret visits to the dungeons with food and medicine, her discussions with the prisoners about Christian doctrine, the incident when she is confronted by her father while taking food to the captives and the food miraculously appears to be roses, Casilda's illness that brings about her trip to Christian Castile, her baptism in Burgos, her healing by the miraculous waters of San Vicente near Briviesca, and her life there as an anchoress through whom God performed many miracles.

I think the book should be read by any adult with a serious interest in St. Casilda because it was written after Borton had accessed very old church documents that recorded the known information and traditions about Casilda. In her afterword, Borton tells the reader some of what she learned from these materials. Borton also visited Casilda's shrine near Briviesca and writes of her observations.

It is difficult, however, to give the book a very strong recommendation as a juvenile novel to be read by the teenage children of traditional Catholics. For one thing, Borton's description of St. Casilda's gifts makes them seem more magical than mystical. More importantly, Borton has pacifist and ecumenist biases that are more than a little Modernist.

It is true that in real life Casilda's father (Al-Mamum, the king of the Taifa of Toledo from 1043 to 1075) had a working relationship of sorts with King Ferdinand I of Leon and Castile. Borton, however, idealizes the relationship in such a way that she neutralizes the cultural and religious differences between the two sovereigns.

Also, Borton has Prince Ahmed renounce his militarism and make a pilgrimage to Mecca, after which he becomes a Muslim holy man. And, she has Ben Haddaj convert to the Judaism of his roots. Borton then tells the reader in the afterword, "There are varying legends about Prince Ahmed, Casilda's brother. Some tell that he became a Christian; others recount that he was cruel and unrelenting to his sister. Sulema, Casilda's nurse, is said to have embraced the cross. There is reason to think that Ben Haddaj existed and was a suitor for Casilda's hand."

Regrettably, Borton continues, "I prefer to think that Ahmed and Sulema remained true to their own religion and that Ben Haddaj died in returning to his own, for this underscores something that was wonderful in eleventh-century Spain -- a kind of primitive ecumenism."

Regrettably too, there is a factual mistake in the novel that must have caused Borton some embarrassment after its publication. In the novel, the wife of Ferdinand I of Leon and Castile (1017-1065) is called "Leonor" when in fact his wife was named Sancha. Leonor was the wife of Ferdinand I of Portugal (1345-1383).

In short, while I am grateful to Borton for making St. Casilda more accessible to English speaking readers, I think teenagers would be better off reading historical accounts and being taught the traditional Catholic view of ecumenism.

Source:

Borton de Treviño, Elizabeth; Casilda of the Rising Moon (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York, 1967), p. 185.

Image:

Civitas Toletana from the Codex Vigilanes (976).

Friday, September 24, 2010

A Visit to Casilda's Shrine

Elizabeth Borton de Trevino, a 20th century writer from California who was fluent in Spanish, visited Casilda's shrine in preparation for a novel about the saint entitled Casilda of the Rising Moon that was published in 1967.

Borton traveled first to Rome, and then to Spain. She visited both Burgos and Casilda's shrine near Briviesca to see what she could learn. At the Cathedral of Burgos, the Canon Librarian found for her "all existing books and chronicles about Casilda" and helped her to "translate the old Spanish into modern idiom" for her notes. At Casilda's shrine, Borton spoke with the priest who was the chaplain.

In an afterword to the novel, Borton wrote about what she learned during these investigations. Here is an excerpt of what Borton had to say:

"She lay, I was told, in a stone tomb in a small church erected upon the site of the hermitage where she had passed most of her life in a remote part of Castile. . . .I must note here that I have read a great deal of information about Casilda on Spanish websites and so far I have not found any asserting that Casilda's body is incorrupt. I have also not found anything that confirms Borton's statement about Queen Isabella. I will continue to look into these matters.

"[At the shrine] was a canyon, ending in a steep cliff face; it was topped by the small church where Casilda's body still lies in its stone tomb. Down below were several caves and the health-giving springs, which are still patronized today. The cave where Casilda is said to have lived and the little promontory where she set up her wooden cross and passed hours in ecstatic visions are shown and are much venerated.

"I went into the church. It was a Sunday and country people from all about had come to attend mass. . . . The sacred vessels, the crucifix, and the Holy Book were on the stone sarcophagus. In it lay the Saracen princess, dead more than nine hundred years. . . .

"La santa had gone about the countryside curing people of their ills, [a local man] told me, but angels had followed her brushing away her footsteps from the road with their wings, so that no enemy might pursue and surprise her . . .

"Her body, [the chaplain] told me, is incorrupt, having become petrified but showing no discoloration or decomposition. However, it is somewhat mutilated because of relics taken from it at the command of Spanish kings and queens who were devoted to her, notably the great Isabel the Catholic. In a special case, there is preserved a long tress of Casilda's hair, a rich dark gold. Some ancient carvings on the walls of the sanctuary -- the older walls around which the later church was constructed -- tell outstanding events in the life of Casilda.

"Afterward, I visited the pozo blanco, the 'white springs,' where Casilda regained her health and where pilgrims come to be cured of their ills today, and the little cave where the Toledan princess lived in absolute poverty.

"Yet, although Casilda is remembered as a holy woman, austere and poor, in the countryside where she worked her miracles and died, memories of her in Toledo and in art galleries show her only as a beautiful princess, dressed in the richest of silks, the darling of her father, the King of Toledo."

Source:

Borton de Trevino, Elizabeth; Casilda of the Rising Moon (Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1967), pp. 183-185.

Image:

Statue of St. Casilda that is in her shrine.

Thursday, September 23, 2010

The Legend of St. Casilda

Casilda is an 11th century Catholic saint who converted from Islam. She is variously known as Casilda of Toledo, Casilda of Burgos, Casilda of Briviesca, and Casilda of the Angels. Her father was the king of the Taifa of Toledo in Spain from 1043 to 1075.

Based on information in Spanish in an online article by Dolores Güell, the legend of St. Casilda is as follows:

Casilda showed special kindness to Christians imprisoned by her father by taking them food hidden in her clothing. Her father, the king, became aware of strange behavior on the part of his daughter, began to spy on her, and surprised her one day on her way to visit the prisoners.Casilda's feast day is April 9. Miracles worked through her intercession that are recorded in church documents include cases of blood flow, falls, and accidents. Relics of Casilda are venerated in the Cathedrals of Burgos and Toledo, and in the Relic Chapel of the Society of St. Pius X in St. Mary's, Kansas. Her remains are at a shrine close to the cave where she lived. The shrine is home to a painted wooden sculpture of Casilda said to be the work of Diego de Siloe.

Sternly, the king demanded to know what she was carrying. "Roses," replied Casilda, as she unfolded her overskirt. It was not that the food actually changed into roses. Rather, by a miracle, the food was made to look to the king like roses. He then gave Casilda free passage and she went on her way with her gifts for the prisoners.

Casilda learned about Christianity during her encounters with the prisoners and was drawn to the Faith but conversion was impossible under the circumstances.

After a time, she fell ill with a blood flow that none of the local doctors could cure. At the suggestion of the Christians, she traveled north to the province of Burgos, a brilliant retinue escorting her.

She sought baptism at Burgos and bathed in the miraculous waters of San Vicente near Briviesca. She prayed fervently and was cured.

After her miraculous healing, Casilda consecrated her virginity to Our Lord and became an anchoress, living a life of solitude and penance in a cave near the miraculous waters where she had been healed. Some sources say that she lived to be 100 years old. Many miracles are attributed to her intercession.

Source:

Güell, Dolores; "Santa Casilda de Toledo" online article

Image:

One of Zurbaran's paintings of Casilda. In the public domain.

Saturday, September 11, 2010

The Five Elements of Floral Design

In addition to Adelaide B. Wilson's discussion of the six principles of floral design, she lists five elements of floral design. The elements are: line, form, pattern, texture, and color. One might think of the six principles as the active components while the elements are the matter on which they act in making the arrangement.

What Wilson has to say about the five elements can be summarized as follows:

Line refers to the overall framework or skeleton of the flower arrangement. It can include many subsidiary lines that are curved or straight, long or short. Wilson recommends working with the natural shape of the stem in creating line, and choosing the natural shape carefully. She cautions against trying to force an unnatural line on a stem as it might not remain in place.

Form refers to the shape of the bloom. Some are elliptical, some trumpet-shaped, others are spiked and so on. Also, the same flower has different forms when it is in bud, in half-bloom, and in full bloom. By using these forms in different combinations, one creates contrast and rhythm as described in the discussion of the six principles.

Pattern is the combination of line and form. It includes how empty spaces interrelate with the stems and blooms. Wilson recommends being careful not to crowd the flowers too closely as this impedes the construction of a pleasing pattern.

Texture refers to the roughness or smoothness of the bloom or foliage. It can be used in addition to color to create contrast. It adds shadow and depth. Wilson recommends being sensitive to the texture of other items in the church and also to whether the plant is so coarse in texture that it is too casual for church flowers.

Color is especially important in relation to rhythm and balance. Wilson points out that the visual weight of a color is significant. Light or pale colors seem lighter in weight than darker ones. Generally, it is better to use light colors high in the arrangement and dark colors lower, so that the dark colors give stability by means of horizontal balance.

Wilson advises the arranger to be sensitive to the liturgical colors. She also cautions that "great masses of brilliant flowers" are improper in a church setting because they draw too much attention. She notes that small amounts of lighter values of warm hues (yellows and reds) are effective for large areas whereas dark values of all colors, and blues and violets in all values, have a receding quality so that they tend to become invisible in a large church or a dim one.

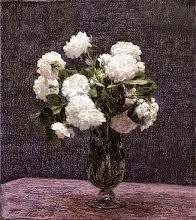

The floral still-life above by Jan Davidsz de Heem illustrates all five elements of floral design. It can be an interesting exercise to use the painting to identify them.

Source:

Based on Wilson, Adelaide B.; Flower Arrangement for Churches (M. Barrows & Co., Inc.; New York, 1952), pp. 62-73.

Image:

Heem, "Flowers in a glass vase" (17th century; oil on canvas), from Wikimedia Commons. In the public domain.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)